Building Solidarity among Gig Workers through Digital Organizing

A new MIC Center report offers recommendations for activists and policymakers.

Photo Credit: @benjamin_1017 / Unsplash

Just days before Uber was set to go public last May with its $91 billion IPO, some of its drivers mounted protests, strikes, and other resistance actions in cities across the globe, including Melbourne, London, and Nairobi. Regardless of the location, the litany of driver grievances largely echoed one another: recent wage cuts, lack of job security and health-care benefits, and most importantly, Uber’s classification of drivers as independent contractors.

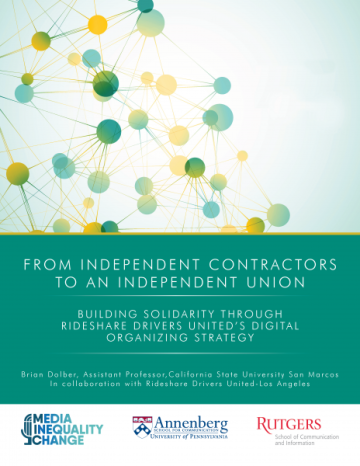

Rideshare Drivers United (RDU), an association of U.S. based Uber and Lyft drivers advocating for better working conditions, was instrumental in the May protests, as well as in strikes held last March. A new report from the Media, Inequality and Change (MIC) Center — a joint project of the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania and the School of Communication and Information at Rutgers University — examines RDU’s organizing strategies and offers recommendations for replicating its success.

Because rideshare drivers are barred from collective bargaining, traditional union organizing is off-limits. In addition, in contrast to laborers who are working together at a factory or plant, rideshare drivers are completely disaggregated and unlikely to know one another. So how do you go about motivating companies to meet the demands of workers?

Brian Dolber, Assistant Professor at California State University San Marcos and the report’s author, worked with RDU-Los Angeles to develop and test a hybrid strategy for organizing rideshare drivers that combines low-cost social media advertising, app-based technologies, and texting with phone calls and in-person meetings. Using these techniques, RDU-LA spent less than $3,000 to generate nearly 1,150 members over the course of three months. These members then planned, organized, and participated in multiple protest actions throughout the first half of 2019.

“By the May 8 strike, RDU had not only built an organization, it had played a major role in sparking a movement,” Dolber said. “The success of RDU’s campaign demonstrates that its model can help overcome the obstacles endemic to building a democratic organization of a massive, unidentified, disaggregated, and fluid workforce.”

RDU’s organizing strategy and protest actions garnered media attention — from the New York Times, NPR, and the Philadelphia Inquirer, among others — which brought the concerns of rideshare drivers into the public conversation and put pressure on companies like Uber and Lyft to change their policies. Dolber and other RDU activists believe that further change can be achieved through additional gig worker organizing and hope the strategies they’ve developed can help activists in other cities or industries build coalitions of workers.

The report, “From Independent Contractors to an Independent Union: Building Solidarity through Rideshare Drivers United’s Organizing Strategy,” includes a detailed analysis of RDU’s strategies as well as recommendations for activists and policymakers. Read the full report here.