How Media Practitioners and Scholars Navigate a Changing World Order

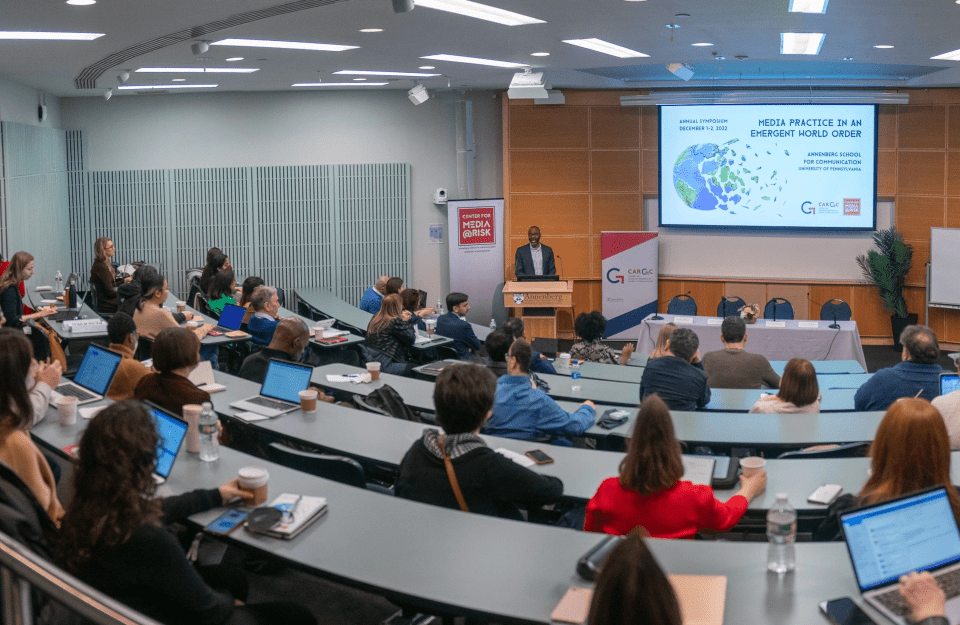

A symposium held by the Center for Media at Risk and the Center for Advanced Research in Global Communication brought together media practitioners from around the globe.

After Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the existing world order abruptly changed. What does that mean for global media?

Every year since its launch in 2018, the Center for Media at Risk at the Annenberg School for Communication has held a symposium on a topic of interest that brings media scholars and practitioners together. This was the first symposium co-hosted with the Center for Advanced Research in Global Communication (CARGC), but the pairing on a global media topic was natural, said Aswin Punathambekar, Professor of Communication and Director of CARGC.

“The Center for Media at Risk is devoted to fostering free and critical media practice, and CARGC produces and promotes scholarly research on global communication and public life,” he said during opening remarks. "With an eye on Russia's recent assault on Ukraine as well as other political and socio-cultural shifts that are recalibrating international relations, our goal is to understand how these shifting contexts shape what media practitioners do and if and how these changing conditions can and do encourage resistance and creativity."

Barbie Zelizer, Raymond Williams Professor of Communication and Director of the Center for Media at Risk agreed. “What media practice looks like when world orders shift has huge implications for all of us on how we imagine ourselves as a collective,” she said. “How we chart the high and low points of everyday life, how we evaluate what's unavoidable, appropriate and morally correct, and most importantly, how we imagine what's possible.”

Hong Kong: Revolution of Our Times

The symposium began with a keynote address by Kiwi Chow, director of Revolution of Our Times, a documentary about the 2019–2020 Hong Kong protests.

The film made its surprise debut at the Cannes Film Festival in 2021 — its inclusion had been kept secret in the months leading up to the event as festival organizers feared retaliation from China. Chow joined the symposium via secure video call and was aided in translation from Cantonese by Alan Yu, a reporter at WHYY in Philadelphia.

Chow discussed the importance of documenting the rupture and fall-out that takes place when world orders are challenged and change. Media practitioners are at the center of these tumultuous moments, risking their lives to report back the information we need to address uncertain terrain.

Shake-up

The symposium’s first panel, “Shake-up”, brought together three media scholars and practitioners from Kyiv, Ukraine to discuss the state of Ukrainian media during the full-scale invasion.

The panel included Yevhen Fedchenko, director of the Mohyla School of Journalism at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy in Ukraine, the co-founder of StopFake.org, and a visiting scholar at the Center for Media at Risk; Olena Lysenko, a documentarian from Kyiv and visiting practitioner at the Center for Media at Risk; Dariya Orlova, a senior lecturer at the Mohyla School of Journalism and a visiting scholar at the Center for Media at Risk; and moderator Liz Hallgren, doctoral fellow at the Center for Media at Risk.

Panelists discussed the ways in which war has disrupted media practice in Ukraine.

Fedchenko zeroed in on combating propaganda, explaining how and why he started StopFake.org, a fact-checking site that dispels myths spread by the Russian government.

“There’s not much media in Russia that can fight back against disinformation,” he said, “so we said, ‘We’ll do it.’”

Lysenko discussed the war’s effect on documentary filmmakers in Ukraine and her hopes for the future of filmmaking in Ukraine.

“Prior to the full-scale Invasion of Ukraine, Ukrainian documentary filmmaking was undergoing a renaissance,” Lysenko said. “After the tumultuous events of 2014 — the Euromaidan Revolution and Russian aggression in Crimea — Ukrainian documentary filmmakers started to attract higher levels of funding from the Ukrainian State Film Agency and greater attention at international film festivals.”

She explained that after the full-scale invasion in February 2022, many Ukrainian documentary filmmakers began to think that cinema is meaningless and that the most important thing to do was to defend Ukraine. Filmmakers joined the armed forces or volunteered to help the army and civilians.

Eventually, more and more documentarians returned to filmmaking, Lysenko said. “They believed that it's their duty to document this war; to broadcast events globally, to collect evidence of Russian war crimes, to ensure that films are there for future generations of artists to work with.”

Personally, Lysenko believes that her most important duty as a journalist and a filmmaker is to inform the world about ongoing events in Ukraine. She worked as a fixer for international correspondents and started filming the impact of the war with her long-time collaborator Jason Blevins.

Their documentary, “I Never Had Dreams of My Son” tells the story of a father looking for his lost son, a Ukrainian soldier who left home to fight pro-Russia separatists in Crimea.

Orlova, a former journalist turned media scholar, discussed the perspective of Ukrainian media practitioners.

”I've been doing research on Ukrainian journalists since the Euromaidan Revolution,” she said, “and I've been trying to see how their professional identity has changed and the issues that they have been dealing with since then.”

She meditated on the panel’s theme — Shake-up. “Shake up in the world order is certainly different for Ukrainian journalists compared to journalists from other countries,” she said. “This disruption is extremely tangible in Ukraine because you see and you feel and you witness real deaths, real destruction, broken lives."

Many Ukrainian journalists have been killed since the full-scale invasion in February and over 100 news outlets had to shut down or stop their work, she said. Paired with this immediate physical danger is the toll on journalists’ mental well-being.

Despite this monumental shake-up, Ukrainian journalists are finding ways to continue their work. “When journalists face this kind of a crisis of professional identity, it can also boost new energy to seek answers rather than follow the familiar paths,” she said.

Undoing

The second panel, Undoing, featured Tikhon Dzyadko, editor-in-chief of Russian television station TV Rain; Wazhmah Osman, associate professor of Media and Communication at Temple University; Matt Sienkiewicz, chair and associate professor of Communication and International Studies at Boston University; and moderator Yuval Katz, postdoctoral fellow at CARGC.

The conversation centered on mediamakers and journalists being forced out of their home countries during conflict.

Osman shared research from her book, Television and the Afghan Culture Wars, discussing the emergence and expansion of Afghan media in post-9/11 Afghanistan — and the recent transformation of Afghan media since the Taliban takeover in August 2021.

"The Afghanistan of today is a very different nation than it was in the 1990s when Afghans were traumatized by the violence and lawlessness of the Civil War and the Taliban were even welcomed in some areas,” Osman says. “This generation grew up with mobile phones, hundreds of radios and television stations, and extensive media markets. Afghans wants a diverse public sphere and representative politics no matter how difficult.”

Sienkiewicz discussed his time following media practitioners in the Palestinian territories and Afghanistan during the early 2000s. He reflected on how their work has changed since the publication of his book The Other Air Force: U.S. Efforts to Reshape Middle Eastern Media Since 9/11 in 2016.

“The Trump presidency changed everything,” he said, “especially in this realm of American involvement in the spaces that I studied. The NGOS that funded projects in the Palestinian territories lost much of their funding and all of their confidence. In Kabul, the Taliban grew increasingly adamant in their targeting of media figures — with special attention to those who worked with American-supported television media outlets.”

Tikhon Dzyadko shared the story of TV Rain, a Russian independent television news network of which he is editor-in-chief. His team relocated to Latvia this year after its website was shut down by the government and the channel was taken off the air. (Since the symposium, TV Rain’s license in Latvia was revoked, but the channel found a new home in The Netherlands, where it received a five-year broadcasting license.)

“Speaking about media in Russia is easy,” Dzyadko said, “because there is no media in Russia anymore. After the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russian authorities forced almost all of the independent journalists to leave the country.”

Fall-out

The final panel, Fall-out, featured Ricardo Corredor, director of communications for Colombia’s Truth Commission; Myria Georgiou, professor of Media and Communications at the London School of Economics; Zoé Samudzi, associate editor of Parapraxis Magazine and assistant professor of Photography at the Rhode Island School of Design; and moderator Florence Zivaishe Madenga, doctoral fellow at the Center for Media at Risk and CARGC.

The discussion emphasized the consequences of conflict, including forced migration as well as efforts toward reconciliation and healing. Corredor spoke about the importance of narratives and media-making in fostering peace and healing. The Commission emerged from the 2016 peace accord between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). During their investigation, Corredor’s team interviewed nearly 30,000 people affected by the six-decade conflict, as part of an effort to bring victims truth, justice, reparations, and non-repetition.

He showed a clip from Después del Fuego, a documentary produced by the Commission.

Georgiou discussed the imaginary “crisis” of migration. Migration is not new or out of the ordinary, she says — and emphasized that mediamakers can end the “migration crisis” by simply questioning that framework.

Migration is often categorized as a crisis when the migrants are considered “dangerous” or “different” from fellow citizens, she says, whether because of race, politics, or other characteristics.

Ukrainian refugees received a warmer welcome in European countries than Syrian refugees because they are seen as familiar, she says.

Samudzi spoke about spectacle in the news and politics — whether through photos of atrocities or TV news programs designed to shock.

Since 2016, public officials and talking heads have been growing more and more comfortable with sharing antisemitic discourse on social media, in articles, and on TV, she said, but reporting on fascism and antisemitism in the U.S. is filled with spectacle, often ignoring the complex racial and social politics that drive fascist movements.

A recent example, she pointed out, is journalists’ reactions to Kanye West’s appearance on InfoWars, which consisted of jokes and statements that Alex Jones was less fascist than Kanye West.

“The scales of antisemitism and euphemistic racism and plausible deniability are seen when we forget that it’s not a matter of whether it actually matters that one person is more antisemitic than the other,” Samudzi said. “Rather, it’s about the recognition of the kind of political euphemism that people are allowed to use in public in order to continue to espouse and to foment antisemitism without getting tanked.”

Closing Remarks

The event concluded with remarks from Zelizer and Punathambekar. Both spoke of the importance of creating media that takes the time to thoroughly consider the complexity of a changing world order — the uncertainty, the instability, the violence, and the reconciliation that occurs.

"It strikes me that media practice tries — even in the best of cases — but particularly in the situations that we've been talking about today, to be more in the here and now, when it should be really into the there and then," Zelizer said.

Punathambekar agreed. "Not surprisingly we've raised more questions than we've answered," he said. “Trying to discern the contours of media practice, let alone the specifics of it in a moment of uncertainty is not easy, but it's clear that it has to be a continual, ongoing thing.”