Local News Volume Does Not Increase Pro-Social Behaviors During COVID-19

A new study from doctoral candidate Sean Fischer shows the limits of local news to overcome nationally polarized issues.

- Local news has also been shown to decrease political polarization at a community level.

- Some issues are so polarized at a national level that local news coverage has little to no influence.

During this pandemic, there are countless voices urging Americans to engage in the kind of civic behaviors that keep us all safe, like social distancing and frequent hand washing. These voices come at the national, state, and local level. But which ones are actually getting through, making it more likely that Americans will comply with the recommendations?

Previous research has found that people are more likely to engage in civic behaviors — like voting, recycling, or when living through a pandemic, wearing a face covering — when their local newspaper includes coverage of these activities. Local news has also been shown to decrease political polarization at a community level. However, a new study from doctoral candidate Sean Fischer suggests that this phenomenon may have its limits.

Fischer’s work suggests that some issues are so polarized at a national level that local news coverage has little to no influence. Specifically, he investigated individuals’ willingness to stay at home in response to the coronavirus pandemic, both before and after statewide stay at home orders were implemented. Surprisingly, he found that local newspaper coverage did not meaningfully affect whether citizens followed social distancing guidelines or not.

“Coronavirus policies are different depending on where you live, and in many places, the guidelines and regulations are changing daily,” says Fischer. “So local news should be playing a key role in providing communities with the information they need to stay safe. I thought this would mean that people with access to a local newspaper would be more likely to stay at home and not view this crisis along partisan lines. But the data doesn’t support that.”

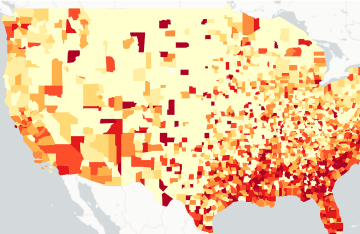

Using a dataset constructed by the University of North Carolina, Fischer identified the number of local newspapers available by county. He then compared this information with anonymized location data collected by Google to determine whether people were staying home in a particular county and if this correlated with the volume of local newspapers. He found that, while the volume of local newspapers increased pro-social behaviors to a small degree, it did not impact citizens’ behaviors as much as partisanship or actual stay at home orders did.

Fischer points out that this is a preliminary finding and that additional research should be conducted to further test these results. For example, many local newspapers are now owned by major conglomerates. Does this lessen the nonpartisan nature of those local newspapers? In addition, many people get their news from television rather than print. How does local television news play into these findings, and is it impacted by the fact that, like local newspapers, many local television networks are also owned by media conglomerates?

Nevertheless, Fischer’s study points to the greater problem of political polarization in America, and the stark differences in beliefs along party lines — even in response to a global pandemic.

Fischer studies how political communication and other forms of information affect civil society, and how political polarization impacts information sharing, voting, and other parts of American democracy. At the Annenberg School, he has served on the 2019 Graduate Student Symposium planning committee, and is a member of the Democracy & Information Group (DIG), led by his advisor, Professor Yphtach Lelkes.