After #MeToo, Sexual Assault Survivors Still Fight To Be Believed

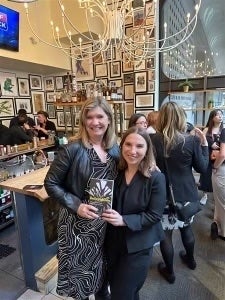

In their new book, Dean Sarah Banet-Weiser and former postdoctoral fellow Kathryn Claire Higgins explore the work victims of sexual violence go through to be believed.

Believability: Sexual Violence, Media, and the Politics of Doubt by Dean Sarah Banet-Weiser and Kathryn Claire Higgins

In the spring of 2022, Johnny Depp alleged that his ex-wife Amber Heard defamed him by calling herself a “public figure representing domestic abuse” in a Washington Post op-ed. The trial that followed became a public spectacle — live streamed, memed, and meticulously picked apart on TikTok and YouTube.

The #MeToo movement had gone viral five years prior and the world was deep in the “post-truth” era. As the trial proceeded, Heard’s every action was scrutinized and used as evidence as to whether or not #BelieveWomen applied to her.

While watching the trial, feminist scholars Sarah Banet-Weiser and Kathryn Claire Higgins were struck by the public’s demand for Amber Heard to be the “perfect victim.” She had to have the “right” tone of voice, the “right” emotions.

In their new book, Believability: Sexual Violence, Media, and the Politics of Doubt (Polity, 2023), Banet-Weiser and Higgins explore how the idea of a “perfect victim” is expressed in contemporary media post-#MeToo and how this narrative intersects with conceptions of race, class, and gender.

The book emerged from conversations between Banet-Weiser and Higgins about what happens “when women are believed about sexual violence in numbers that we haven't seen before, and yet there's a narrative circulating at the same time that says, ‘You can't believe anyone; everything is a lie,’” says Banet-Weiser, Dean of the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania.

In this cultural moment, believability is a commodity that sexual assault victims are expected to acquire through money, status, performance, or a litany of other means, Banet-Weiser and Higgins explain. Media is obsessed with showing who is worthy of being believed and who is not and victims are supposed to use this as instruction.

“Women have to work to be believed,” Banet-Weiser says, “and women with marginalized identities have to work harder. Historically, women are seen to be inherently untrustworthy and men are seen to be inherently truth tellers.”

In Believability, Banet-Weiser and Higgins present an “economy of believability” based on the work that survivors of sexual violence do to “become believable,” and the media that shapes this work.

Believability on Screen

The struggle to be believed is depicted in the flood of television shows and movies about sexual violence that cropped up after the #MeToo movement took off, Banet-Weiser and Higgins point out in Believability.

One of those productions is Unbelievable, a miniseries on Netflix. In it, a teenage girl named Marie reports she was raped and is at first believed, then quickly isn't. After police, friends, and family show suspicion when she doesn’t act like the perfect victim — doesn’t show enough emotion or misremembers a detail while retelling her testimony — she retracts her statement and her rapist goes on to assault more people.

This show, based on a true story, encapsulates what often happens when a victim of sexual assault doesn’t perform believability perfectly.

In a pivotal moment in the show, Marie is speaking with her therapist, who asks how she would handle the situation if it happened again. Marie answers that she’d tell a simple story that people would find believable, because “if the truth is inconvenient…they don’t believe it.”

Believability on the Shelves

The “economy of believability” naturally plays out in how women are expected to spend their money, Banet-Weiser and Higgins explain.

Marketers offer many products designed to help women become believable before an assault even happens: nail polish that changes color if you’ve been drugged; scrunchies that double as drink covers; “cute” tasers and pepper spray.

“Marketing anti-sexual violence products and services to women is part of a longer trajectory of making women responsible for their own assaults,” says Higgins, lecturer in Global Digital Politics in the Department of Media, Communications and Cultural Studies at Goldsmiths, University of London. “It hinges on the idea that your liberation, your safety, your believability, are all within your grasp if only you work hard enough and consume in the correct way.”

Like much of the media that depicts stories of sexual violence, these products often “end up reinforcing rather than challenging an unevenly gendered and racialized economy of believability,” Banet-Weiser and Higgins write.

Backlash against #MeToo

As they wrote Believability, Banet-Weiser and Higgins observed the dialogue around #MeToo shift from “an urgent public discussion about endemic sexual violence and sexual assault” to an “anxious conversation about the politics of public accusation and when or if someone should or should not be allowed to speak out about sexual assault,” Higgins says.

More and more, public discourse around sexual violence is fixating on the believability of and sympathy for men accused of sexual assault, who don’t have to be the perfect victim to be believed, just a “good guy.”

“Doubt works differently for different kinds of subjects,” Banet-Weiser and Higgins write in the book. “For powerful men facing public allegations of sexual harassment and assault in the mediated public sphere…even a small amount can function effectively as exoneration. Women and other marginalized subjects, however, must usually wholly overcome doubt to access belief and public solidarity.”

Women are encouraged to use consent apps, keep screenshots of DMs from would-be sexual assailants, to text friends when their Uber gets them home safe, to have evidence constantly on hand, while men are encouraged to keep their reputation clean.

Moving Forward

In the summer of 2022, Amber Heard was found liable for defamation, even though she had never mentioned Johnny Depp by name in her op-ed.

“What’s interesting about the Depp/Heard case is that the people who were trying to discredit Amber Heard were not actually trying to discredit her testimony of abuse necessarily,” Higgins says. “It was about positioning her as someone who wasn't deserving of public sympathy.”

Banet-Weiser and Higgins see the demands for women to be believable play out over and over again — as another trending hashtag appears, another story drops.

“In the current moment, there’s the idea that if we can just find better ways to prove sexual assault, then that will address the issue of believability, says Higgins. “But the problem has never been that sexual assault is too hard to prove, it's that people care too little about it. They're not invested in whether or not this is a true experience, either for individuals, or for women and other marginalized people in general.”

Believability: Sexual Violence, Media, and the Politics of Doubt is available now from Polity Press.