Americans Don’t Understand What Companies Can Do With Their Personal Data — and That’s a Problem

A new survey of 2,000 Americans finds that people don’t understand what marketers are learning about them online and don’t want their data collected, but feel powerless to stop it.

Have you ever had the experience of browsing for an item online, only to then see ads for it everywhere? Or watching a TV program, and suddenly your phone shows you an ad related to the topic? Marketers clearly know a lot about us, but the extent of what they know, how they know it, and what they’re legally allowed to know can feel awfully murky.

In a new report, “Americans Can’t Consent to Companies’ Use of Their Data,” researchers asked a nationally representative group of more than 2,000 Americans to answer a set of questions about digital marketing policies and how companies can and should use their personal data. Their aim was to determine if current “informed consent” practices are working online.

They found that the great majority of Americans don’t understand the fundamentals of internet marketing practices and policies, and that many feel incapable of consenting to how companies use their data. As a result, the researchers say, Americans can’t truly give informed consent to digital data collection.

The survey revealed that 56% of American adults don’t understand the term "privacy policy," often believing it means that a company won't share their data with third parties without permission. In actual fact, many of these policies state that a company can share or sell any data it gathers about site visitors with other websites or companies.

Perhaps because so many Americans feel that internet privacy feels impossible to comprehend — with “opting-out” or “opting-in,” biometrics, and VPNs — they don’t trust what is being done with their digital data. Eighty percent of Americans believe that what companies know about them can cause them harm.

“People don't feel that they have the ability to protect their data online — even if they want to,” says lead researcher Joseph Turow, Robert Lewis Shayon Professor of Media Systems & Industries at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania.

What Americans Know — or Don’t

Americans often encounter the idea of “informed consent” in the medical context: for example, you should understand what your doctor is recommending and the possible benefits and risks before you agree or disagree to a procedure.

That same principle has been applied by lawmakers and policymakers with respect to the commercial internet. People must either explicitly “opt in” for marketers to take and use data about them, or have the ability to “opt out.”

This presupposes two things: that people are informed — that they understand what is happening to their data — and that they’ve provided consent for it to happen.

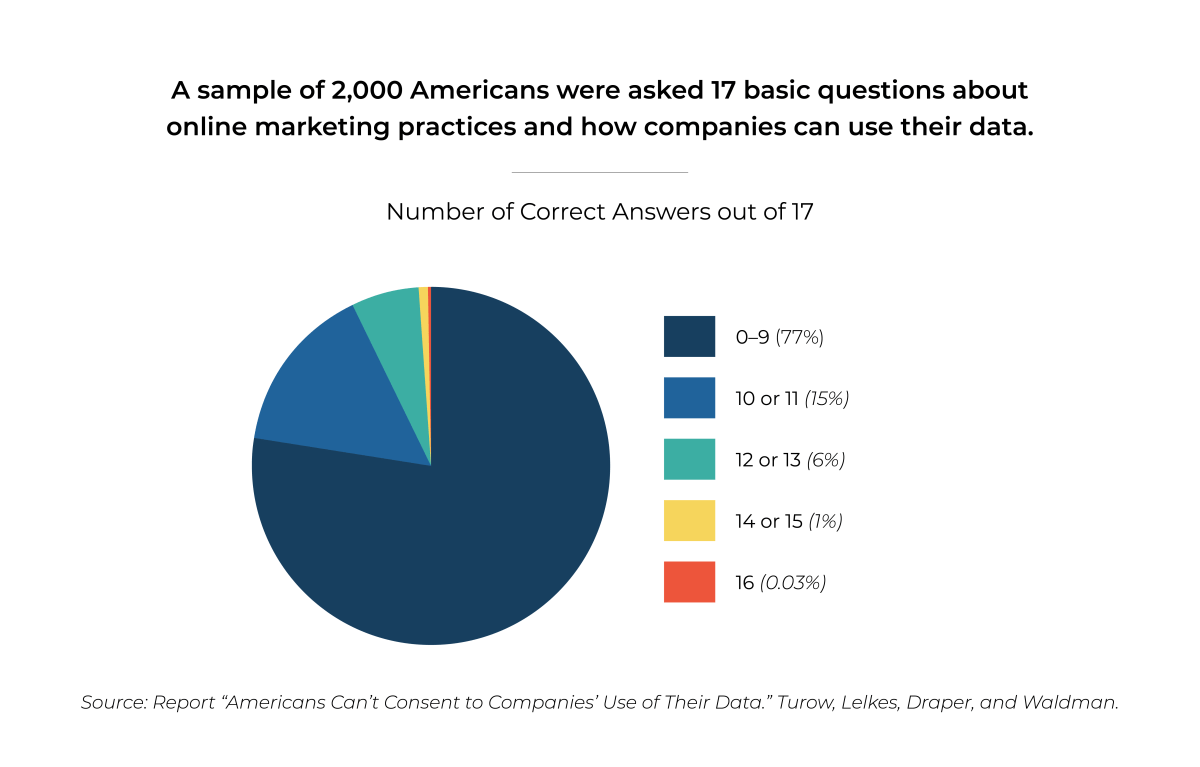

In order to test both of these elements, the survey presented 17 true/false statements about internet practices and policies and asked participants to mark them as true or false, or indicate that they did not know the answer.

Statements included, “A company can tell that I have opened its email even if I don’t click on any links” (which is true) and “It is illegal for internet marketers to record my computer’s IP address” (which is false).

Fully 77% of those surveyed answered 9 or fewer questions correctly — a failing grade in a typical classroom. Only one person in the entire 2,000-person sample would have received an “A” on the test.

Nevertheless, the survey provided many insights into Americans’ digital knowledge — or lack thereof:

- Only around 1 in 3 Americans knows it is legal for an online store to charge people different prices depending on where they are located.

- More than 8 in 10 Americans believe, incorrectly, that the federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) stops apps from selling data collected about app users’ health to marketers.

- Fewer than one in three Americans know that price-comparison travel sites such as Expedia or Orbitz are not obligated to display the lowest airline prices.

- Fewer than half of Americans know that Facebook’s user privacy settings allow users to limit some of the information about them shared with advertisers.

“Being wrong about such facts can have real consequences,” the report notes. For example, a person who uses a fertility app to facilitate family planning may not realize that U.S. health privacy laws don’t prevent the app from selling their fertility data to a third party. In addition, retailers can sell data on who has shopped for fertility-related items, and in many cases, internet service providers can sell your browser search history.

What if your employer or health insurer had that information? In the wake of the Dobbs decision that allows states to regulate abortion, experts also fear that the availability of this seemingly personal data may leave individuals legally vulnerable as well.

“We the Resigned”

In this study, and others Turow and colleagues have conducted in the past, virtually all Americans agree that they want to have control over what marketers can learn about them online. But at the same time, they see that outcome as virtually impossible.

This belief that control is out of your hands and that it’s pointless to try and change a situation, is called resignation, Turow says. Most Americans are resigned to living in a world where marketers taking and using your data is inevitable.

And Turow has seen a large uptick in resignation to privacy intrusions among Americans. In 2015, his research showed that 58% percent of Americans were resigned. Now that figure is up to 74%.

“The levels of resignation and the levels of distrust are huge,” he says. “Only 14% of Americans believe that companies can be trusted to use their data with their best interests in mind, so the vast majority of people who use the internet are essentially relinquishing their data to entities that they don’t trust.”

Calling on Congress to Act

The study found that nearly 80% of Americans believe it is urgent for Congress to act now in order to regulate how companies' can use personal information.

“We live in a society where there's a sea of data collected about individuals that people don't understand, know they don’t understand, are distrustful of, resigned to and believe can harm them,” Turow says. “At the same time, the kinds of technologies that are being used to track people are getting more sophisticated all the time.”

He worries that the longer governments wait to change things, the harder it will be to control any of our data.

“For about 30 years, big companies have been allowed to shape a whole environment for us, essentially without our permission,” he says. “And 30 years from now, it might be too late to say, ‘This is totally unacceptable.’”

Conclusions and Solutions

To date, privacy laws have been focused on individual consent, favoring companies over individuals, putting the onus on internet users to make sense of whether — and how — to opt in or out.

“We have data now that shows very strongly that the individual consent model isn’t working,” Turow says.

He and his co-researchers suggest that policymakers “flip the script” and restrict the advertising-based business model to contextual advertising, where companies can target people based only on the environment in which they find customers. For example, if you visited a website about cars, automotive-related companies would be allowed to display advertisements to you, though without any data on your individual behavior on that website.

The researchers realize they are calling for a paradigm shift in information-economy law and corporate practice, but believe consumers deserve dramatically more privacy than they currently have — and should get it without the burden of becoming technology experts.

Turow hopes that this research will jumpstart a new conversation about privacy and consent — one that will encourage individuals to shake off their resignation.

“It can feel too late to change things,” Turow says, “but I think we should try.”

The report is entitled, “Americans Can’t Consent to Companies’ Use of Their Data: They Admit They Don’t Understand It, Say They’re Helpless To Control It, and Believe They’re Harmed When Firms Use Their Data – Making What Companies Do Illegitimate.” In addition to Turow, authors include Yphtach Lelkes (Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania), Nora A. Draper (University of New Hampshire), and Ari Ezra Waldman (Northeastern University). Funding for the project came from an unrestricted grant from Facebook, which was not involved in the research.