CDCS Digital Launch Embodies the Ascendant Influence of Digital Culture

The event highlighted new ways of thinking about digital technology and society.

It wasn’t planned that way, but there was something fitting about the Center on Digital Culture and Society (CDCS) moving its launch event online. After all, at its essence, digital culture is about the way that our physical, social, and emotional lives are impacted by the internet and technology. As much of the world finds the need to be physically distant in response to COVID-19, our digital lives have taken on unprecedented importance.

In its April 3 launch event, Social Justice and the Remaking of Technological Cultures, CDCS not only discussed new ways of thinking about digital technology and society, but did so in a format that itself helped participants explore how new forms of digital interaction under COVID-19 are changing society.

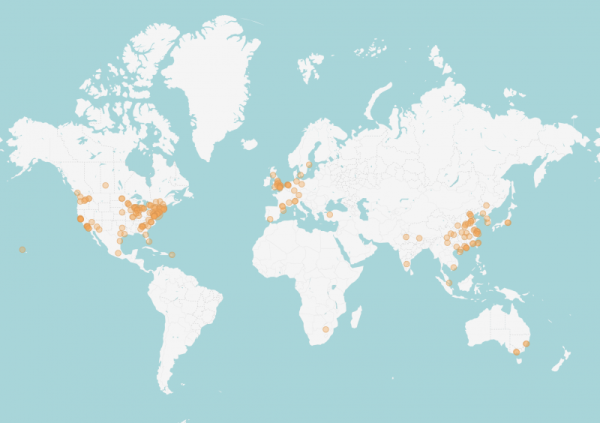

Mediated by the online conferencing platform Zoom, scholars from as far away as Australia, China, and Amsterdam tuned in to hear presentations on a diverse range of topics including the digital technologies used by protesters in Hong Kong; how apps and social media can combat racial injustice and gender violence; how algorithms use our data in troubling ways; and how digital media are reshaping labor markets around the world.

“Our speakers painted a collective vision for critical scholarship on digital culture and society which highlighted historical and comparative analysis, complex and relational thinking, and sensitivities to research as ethical and political praxis,” says CDCS Director Guobin Yang, the Grace Lee Boggs Professor of Communication and Sociology at Penn. “Their insights will guide us as we plan more focused thematic explorations in future CDCS projects and events.”

In the keynote address, “Are Digital Cultures Choice or Fate?”, Craig Calhoun, University Professor of Social Sciences at Arizona State University spoke to the work of each presenter as he addressed how the current COVID-19 crisis puts societies and their digital cultures at a point of inflection. The loss of physical public spaces calls into question what it means to talk about “the public.”

“It is an illusion to think we can value our zones of autonomy independent of large-scale systems and their radical inequalities,” said Calhoun. “Sheltering in place is not comfortable or violence-free for everyone, and not everyone can do it.”

Interestingly, there was a major upside to a digital conference: What would have been an in-person event for 60 or 70 people at most became an online event that at its peak drew 130 people watching simultaneously, with many more dropping in throughout the day. More than 500 people registered, hailing from five continents.

The switch, of course, required some scrambling.

After spending nine months planning the in-person event, CDCS Associate Director Rosemary Clark-Parsons confesses that three-and-a-half weeks before the event, she found herself Googling “how to host a webinar.” After landing on Zoom as a platform, she then had to prepare 12 presenters, four moderators, three introduction-givers, and a keynote speaker for how an online conference is different than a conventional one.

She encouraged them to shorten their presentations and draw as much as possible from visual material as a way to keep the audience engaged. She also had to gauge their comfort with the technology. She created an FAQ guide and ran several practice sessions. It paid off: On the day of the event, the conference came off without a hitch.

“It was the best Zoom-based intellectual conversation I have ever seen, and probably the best of any virtual or non-virtual conferences I’ve known in recent years,” says Yang.

One participant in the United Kingdom reached out to Yang on the Chinese social media platform Weibo after the conference to say that the event offered them both mental stimulation and a chance to feel released from the unsettling environment of coronavirus lockdown.

While Yang and Clark-Parsons intended to structure the conference as four separate corners of the field, many connections emerged throughout the day, with panelists referencing each other as well as overlapping theory.

“The conference pointed to the need for spaces where we can see connections across what might initially seem like distant corners of scholarship in the area of digital media studies,” says Clark-Parsons. “This is exactly why we started CDCS: to foster interdisciplinary dialogue and scholarship.”

Conference presenters included Meredith Clark (University of Virginia), Jun Liu (University of Copenhagen), Jen Schradie (Sciences Po), Moya Bailey (Northeastern University), Kishonna Gray (University of Illinois at Chicago), Carrie A. Rentschler (McGill University), Angelé Christin (Stanford University), Ezekiel Dixon-Román (University of Pennsylvania), Joseph Turow (University of Pennsylvania), Brooke Erin Duffy (Cornell University), Ben Shestakofsky (University of Pennsylvania), and Lin Zhang (University of New Hampshire). In addition, the University of Pennsylvania’s David Grazian, Sarah J. Jackson, Jessa Lingel, and Julia Ticona moderated panels; Yang and Annenberg Dean John L. Jackson, Jr. introduced the day; and Annenberg School Professor Barbie Zelizer introduced the keynote speaker.