Navigating the Intersection of Media and Social Justice

A symposium held at Annenberg took a deep dive into what happens when media practices, values, infrastructures, or ownership pose risks to social justice.

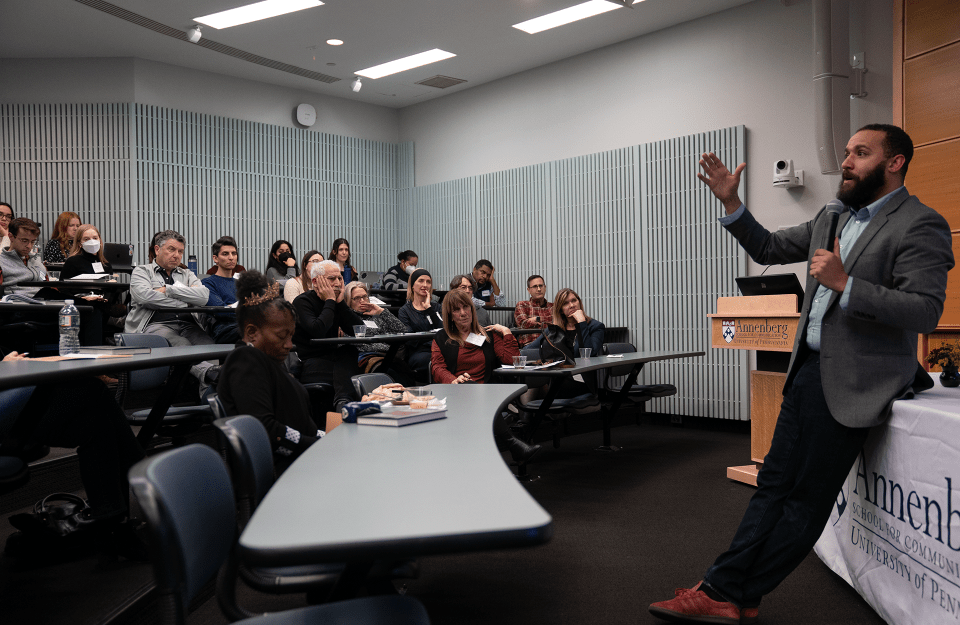

Wesley Lowery delivers the keynote at the “When Media Put Social Justice at Risk” symposium.

At its best, media shines light on injustices, ensures transparency between leaders and the public, and prevents abuses of power. At its worst, it thwarts those efforts.

On November 30 and December 1, a symposium at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania brought together scholars and media-makers to delve into the ways in which media can deliberately or unintentionally hinder the progress of social justice efforts, as well as the ways in which it can assist and extend those causes.

Entitled “When Media Put Social Justice at Risk,” the two-day event was co-organized by the Center for Media at Risk and the Annenberg Center for Collaborative Communication (C3), a joint center of the Annenberg Schools at Penn and USC.

Since its launch in 2018, the Center for Media at Risk, directed by Raymond Williams Professor of Communication Barbie Zelizer, has held an annual symposium on a topic of interest that brings media scholars and practitioners together. This was the first symposium co-hosted with C3, directed by Sarah Banet-Weiser, the Walter H. Annenberg Dean of the Annenberg School. Focusing on the media and social justice, said Zelizer, was an opportunity for the centers to join efforts in thinking critically about current risks to social justice and the media’s role in shaping them.

Democracy and Journalism

Pulitzer Prize winning journalist Wesley Lowery opened the symposium with a keynote address asking, “What’s the role of the press in a multiracial democracy?”

His new book, American Whitelash: A Changing Nation and the Cost of Progress, explores “whitelash” in the U.S. — the concept that every leap forward in dismantling white supremacy is matched by a push back from the people, structures, and institutions that benefit from it.

Lowery spoke of the need for media outlets to reckon with their past — years when there were no Black writers on staff at newspapers and no Black voices in magazines — and commit to being better than that.

“We have to think about the media as an institution with values,” he said. “If this institution seeks and strives to uphold a standard of multiracial democracy and multiculturalism, it must make decisions different than those when its job was to be an institution that served and upheld a white supremacist status quo.”

Exploring Context

On day two of the symposium, Alicia Bell, Director of the Racial Equity in Journalism Fund at Borealis Philanthropy, also spoke about the racism embedded in the American press, noting that the editor of the first newspaper in the country penned an op-ed calling Black people “great Thieves, much addicted to stealing, Lying, and Purloining.” This narrative persists to this day in the media and the only way it can begin to dismantle this racism is through the practice of media reparations, “the structural, institutional, and policy-level changes needed for a multiracial democracy where everyone thrives,” Bell said.

Next, Alison Hearn, Professor in the Faculty of Information & Media Studies at the University of Western Ontario and Visiting Scholar at the Annenberg Center for Collaborative Communication (C3), argued that emerging financial technology (FinTech) is a form of media in itself that thwarts social justice. She used the example of JUMO, a South African FinTech firm that provides loans via mobile phones. JUMO characterizes their customers — "unbanked” people in the Global South — as ignorant, uninformed, and even “cognitively-impaired” due to poverty, she said. And as FinTech platforms pop up across the Global South, they will continue to perpetuate this neo-colonial messaging, she warned.

Following Hearn was Kelli Moore, Associate Professor of Media, Culture, and Communication at New York University, who spoke of a type of journalism not widely distributed: court watching. She noted that because cameras are forbidden in U.S. courtrooms, court watching (a practice in which regular citizens attend hearings and document what they see and hear) is a crucial way to fill in gaps of information about America's legal processes.

Closing out the panel was Allissa V. Richardson, Associate Professor of Journalism and Communication at USC Annenberg. Inspired by the James Baldwin quote, “Black people need witnesses in this hostile world,” Richardson developed the theory of Black witnessing — looking at the facets of journalism that document the experiences of Black people in America.

Black witnessing has gone through three eras, Richardson says: witnessing slavery through slave pamphlets and abolitionist newspapers; witnessing lynching through newspapers and photographs; and witnessing police brutality through smartphones and social media. She spoke of the challenges to Black witnessing in the current era, from threats towards those filming police to backlash from government officials. Richardson claims that if we look at history, witnesses will always find a way to document their era.

Looking at Conditions

The second panel of the day focused on the political, economic and legal conditions that support media platforms. At the start of the panel, two scholars from Goldsmiths, University of London spoke about the influence of the tech sector on media: Natalie Fenton, also Visiting Scholar at the Annenberg Center for Collaborative Communication (C3) and Gholam Khiabany.

Fenton, professor of Media and Communications, argued that the capitalist values of big tech have taken over media and are stymying social causes. News is shaped by what goes viral on social media, she said, and “thrives on sensationalism, feeds off clickbait, fragments debate, and fosters extremism.” Fenton suggests if we want media that enhances efforts towards social causes, we need to root it in social and communicative justice.

Khiabany, Reader in Media and Communications, claimed that social media thwarts rather than empowers marginalized voices. “There’s a well known claim that social media give voice to individuals by seeming to allow everyone to be the media, free from all constraints,” he said, “but the internet does not increase feelings of security, personal freedom, and influence for marginalized people.” Khiabany argues instead it has emboldened far-right and authoritarian voices that have spilled over to the mainstream media.

Wazhmah Osman, Associate Professor of Media and Communication at Temple University and Visiting scholar at the Center for Media at Risk and the Center for Advanced Research in Global Communication, spoke about the differences in Afghan and U.S. media coverage of the American war in Afghanistan. American television stations tend to censor violence, Osman said, while Afghan television stations broadcast uncensored violence, even during primetime slots. She believes that showing the realities of warfare, even on the TV during dinner time, is key to an accountable and democratic press.

Examining Consequences

The symposium finished with a meditation on the consequences of putting social justice at risk through media and ideas on how to create a more just media system.

André Brock, Associate Professor of Media Studies at the Georgia Institute of Technology, spoke about Black Twitter as a public sphere and how it has outlasted attempts to stymie social justice causes from Elon Musk.

“Institutional and ideological hindrances at Twitter have failed to gain sufficient traction with Black Twitter's digital diaspora,” he said. “It turns out that Twitter's Black DNA isn't just technical, it's also social and cultural.” Brock proposes that media could learn from Black Twitter, a public space that thrives even on a privately owned platform.

Next, former Head of Trust & Safety at Twitter, Yoel Roth, who is the Knight Visiting Scholar at the Center for Media at Risk, spoke about the potential of federated social media, like Mastodon, as a way to spread news about activism and social justice. In order for these decentralized social media platforms to succeed, they need to keep their users safe, Roth said, and one way to do that is to pay content moderators, something these platforms don’t tend to do.

Francesca Tripodi, Assistant Professor at the UNC School of Information and Library Science, shared her research on how ads and search engine optimization (SEO) can keep internet users from finding the information they seek. She explained how crisis pregnancy centers in the U.S. use SEO to make users think they offer abortion care when their actual goal is to deter people from having abortions. When internet users search for abortion care on Google, they are not finding the health services they want, and “ultimately, these discrepancies in user intent have long lasting consequences,” she said.

Journalist Lewis Raven Wallace closed the symposium by discussing the problem of “bothsidesism” in the media. He argued that pressure on journalists to be perceived as objective and unbiased creates a “platform to bigotry and disinformation and can reinforce polarization.”

One countermeasure to this is grassroots journalism, he said, and encouraged media practitioners to learn from, lift up, and shift resources toward these outlets, which are run by and feature marginalized voices.

“The most celebrated journalism has always insisted on representing truthful narratives that accurately convey lived experience,” he said. “We need to amplify sources who have the most insight into an issue, which is often those who are on the ground and conveying outrage at people's dignity being disrespected.”

Transcripts and videos from the symposium are available on the Center for Media at Risk website.

Doctoral students Cienna Davis and Valentina Proust as well as doctoral candidate Louisa Lincoln served as moderators.