Selling the American People: Q&A with Lee McGuigan (Ph.D. '18)

In his debut book, the UNC Hussman assistant professor delves into how data-driven marketing is entrenched in the daily interactions of people, products, and public spheres.

Lee McGuigan with his dissertation chair Professor Joseph Turow

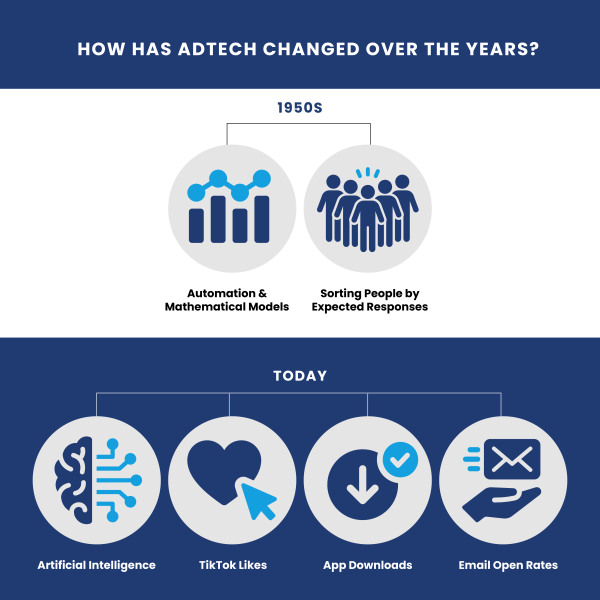

Contemporary advertising is driven by data, as marketers track TikTok likes, app downloads, and email open rates in order to calculate how to sell everything from toilet paper to frozen pizza.

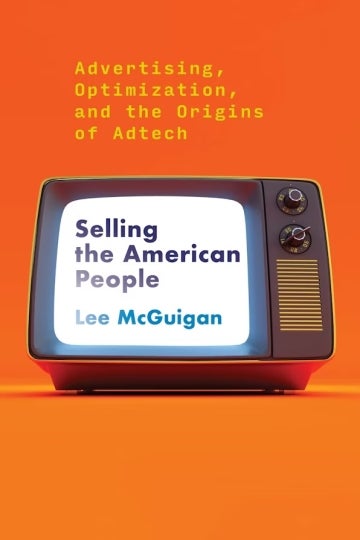

In his new book, Selling the American People: Advertising, Optimization, and the Origins of Adtech, Annenberg alum Lee McGuigan (Ph.D. '18) traces the history of digital advertising and shows how data-driven marketing emerged in the 1950s when ad agencies began using computers and mathematical models to “optimize” their work.

Adtech, short for advertising technology, is pervasive in all areas of our lives, McGuigan says, comprised of the systems that advertisers use to decide which ads to run and to whom, from click trackers to AI models that predict which image will encourage you to buy a product.

Advertisers have always relied on data to make these decisions, McGuigan says, but with the advent of computers, marketers’ ability to collect and process data became more and more precise, launching the age of “big data” before Google even existed.

We recently spoke to McGuigan, assistant professor at the Hussman School of Journalism and Media at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, about the book, which is available now from MIT Press.

Where does the title “Selling the American People” come from, and how does it relate to the themes of your book?

I came across the phrase in an article reporting on a speech by a TV executive in the 1950s; he was talking about the power of TV to persuade viewers to buy advertisers’ products. I found it useful because its syntax invites us to think of both selling things to audiences and selling audiences to advertisers. My book is about how those twin processes — accelerating the circulation of commodities and turning moments of attention into investment opportunities — are key forces behind the development of seemingly new forms of “adtech.”

How did advertisers use data to “optimize” ads before the internet?

Advertisers and the ad agencies working for them have used data for well over a century to inform strategic decisions and to tell authoritative stories about those decisions (and the decision makers). In the mid-20th century, ad professionals took to using digital computers to, among other things, make seemingly smarter choices about how to spend advertising budgets on media placements so as to maximize financial returns for advertisers. Basically, using automation and mathematical models, the industry tried to get better at predicting and measuring the value of advertising opportunities and efforts — and to do that all much faster than before.

A lot of digital advertising is focused on putting consumers into categories — age, interests, etc. — and then marketing to those specific groups. Does this influence how the media addresses people as a whole?

For decades before the internet became popular, ad-supported media industries were sorting people into populations that were made to represent their perceived value and expected responses to certain types of messages. The whole logic of the system is about producing and circulating “content” that will organize the attention of profitable populations (whether in bunches or as individuals).

How do you predict advertising and consumer surveillance will evolve with the rise of AI technology?

A lot of surveillance and discrimination processes will intensify. AI is already being promoted as a solution to adtech’s privacy problems. But it doesn’t fix those problems, and the fascination with AI is likely to enrich already dominant companies who own or control unmatched data assets, computing power, and infrastructural bottlenecks. And the same themes that were used to herald the power of automation and optimization in advertising in the mid-20th century are being reanimated to dramatize AI. It’s the latest act in a long-running play.